Home - Search - Browse - Alphabetic Index: 0- 1- 2- 3- 4- 5- 6- 7- 8- 9

A- B- C- D- E- F- G- H- I- J- K- L- M- N- O- P- Q- R- S- T- U- V- W- X- Y- Z

Taming the Fire

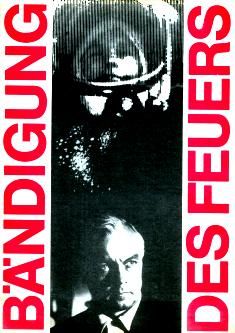

Taming of the Fire Title for the German release of 'Taming of the Fire'. |

With the triumph of the Apollo moon landings in 1969, the prestige of the Soviet space program was at low ebb. Realistic space films -- 'Countdown' and 'Marooned' were being released in the United States. The Soviet leadership must have felt the time had come to make an epic portrayal of the socialist struggle to conquer space for the people. The result, 'Taming ' the Fire', directed by Daniil Khrabrovitsky, was released in the Soviet Union in 1972. It was the first motion picture to deal with the history, lives, and accomplishments of the engineers that had created that nation's space program. Launch sequences were filmed at the Baikonur cosmodrome. All of this was a tremendous sensation at the time, for both the history of Soviet rocketry and extensive footage of the cosmodrome had not been released to the public.

The director, Khrabrovitsky, had made previous films with strong heroes on technical subjects. Khrabrovitsky had dealt with similar material in 'Nine Days of a Year', which covered development of the atomic bomb in Russia. 'Taming the Fire' centered on the life of chief rocket designer Korolev, embodied in the character of Andrei Bashkirtsev, played by Kirill Lavrov. Korolev had died unexpectedly in 1966 at the height of his powers. His death removed the veil of secrecy that had enshrouded him, and his life story could be made public.

The film begins with Bashkirtsev having to fight all the way to the Kremlin to get a key space probe launched on schedule. It then flashes back to his life history. He is shown as an engineering student, constructing home-built gliders. The early experiments of the GIRD rocket enthusiasts are shown, as well as a prophetic meeting with rocket pioneer Tsiolkovskiy. After wartime engineering service, Bashkirtsev supervises development of ever-more powerful rockets, culminating in the launch of the first man into space.

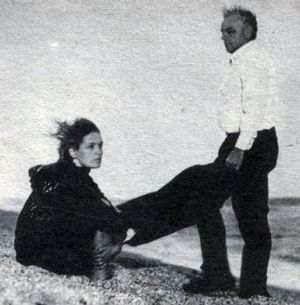

The emotional conflict in the film comes in the relationship between Bashkirtsev and his wife, Natasha. This was a key theme of the filmmaker, how to reconcile the awesome dedication required to be a Communist leader of men with a home and family life.

However all of this had little to do with the real life story of Korolev. 'Sensitive aspects' of Korolev's life were obviously not considered fit topics for Soviet audiences. These included Korolev's imprisonment and near-death in the Soviet Gulag, his work in the prison engineering units during the war, his expeditions to Germany after the war to obtain the secrets of the German V-2, and the huge disputes between him and other Chief Designers that paralyzed the Soviet space program in the 1960's. Hollywood is often accused of twisting the truth in order to 'improve the story' when making historical or biographical films. The tale of the making of 'Taming the Fire' provides an interesting insight into how similar changes, for ideological and censorship reasons, were made in Soviet films.

In 1970 Boris Chertok was named the first non-military consultant to Mosfilm for the movie. Chertok was Deputy Chief Designer at Korolev's design bureau. Chertok liked Khrabrovitsky immediately, and explained to him the technical side of the rocketeer's work - 'the creative kitchen'. He also discussed the extraordinarily interesting figure of Korolev. Chertok was given the first, naïve, version of the screenplay to review. He quickly covered it with notes 'that never happened' or 'that was impossible'. After reviewing these with Khrabrovitsky, he finished by pointing out that Korolev died in a Kremlin hospital, not on the dusty side of a road.

Khrabrovitsky replied that this was HIS vision. "Did Chapaev die as shown on film? Does anyone think that the massacre of the mutineers of the Battleship Potemkin on the Odessa Steps as portrayed by Eisenstein was historically correct? Or the portrayal of the revolutionary figures in 'Armed Men', or 'Lenin in October' or 'Lenin in 1918'? Everyone knows that these were not true. Characters such as Sverdlov and Stalin appear and then disappear from the events portrayed in these films depending on when they were made. We are dealing with films here, not documentaries. Even Tolstoy took liberties with history in his novels. I am not portraying Korolev, but a character of my invention named Bashkirtsev, not Glushko, but Ognev, not Ustinov, but Logunov, not Nedelin, but Vladimirov. Only for the Voskresenskiy character of Stretensky have I even retained a real first name -- Leonid.

Chertok could only retreat from Khrabrovitsky's dogmatic approach. Chertok wanted to have the political repression to which Korolev and Glushko were constantly subjected mentioned in the script , but he was ridiculed by the other consultants. Deputy Chief of Staff of the Rocket Forces Col-Gen Grigoryev told him, "I am always amazed how naïve you specialists are about politics. Who would sit still for such stuff in our theatres? People want to see launches of mighty rockets, while we wait apprehensively in bunkers expecting the shrapnel of the exploding rocket, or our dreams of spaceflight -- portrayals of political repression have no place in film. We want people to see our film, not create controversy".

Khrabrovitsky very much wanted to show the early, romantic days of Korolev's life -- when he built gliders and the early days of rocketry at GIRD. Chertok put him in touch with rocket pioneers Isayev and Tikhonravov for this purpose. Isayev discussed with Khrabrovitsky the days of his youth, when he developed his first engines for rocket fighters in Magnitogorsk. From these stories Khrabrovitsky synthesized his hero, who was a bit of Korolev, a bit of Isayev, and a bit of Tikhonravov. Finally Khrabrovitsky's hero developed into a totally fictional character who had nothing in common with Korolev or Isayev.

Isayev's bureau assisted Mosfilm in construction of a functioning model of a rocket like that used in GIRD's first launches. But this model was naturally much more reliable than those launched by Korolev and Tikhonravov in the twenties!

Chertok was particularly revolted by the warm relationship between Bashkirtsev (Korolev) and Ognev (Glushko) portrayed in the script. In reality their bitter feuds had cost the Soviet Union the moon race. Ognev was not only shown never to have had any conflict with Bashkirtsev, but even kowtowing to what was portrayed as his idol. Khrabrovitsky was determined to portray his heroes as highly cultured and sensitive individuals, not cold technocrats. Ognev was portrayed as having a sensual dependence on Bashkirtsev. Chertok desperately tried to talk Khrabrovitsky out of this portrayal, but the complex reality of life did not fit in with Khrabrovitsky's 'vision'. So in the final film they were still portrayed as close friends.

Even Isayev disagreed with Chertok. He blamed Mishin as the instigator of the bad blood that existed between Korolev and Glushko. He pointed out that this only developed in the 1960's, that up to development of the R-7 they had worked together as a team, first in Kazan in the prison engineering unit, then in Germany, then in the development of the R-1, R-2, R-5 and R-7. In Isayev's analysis Korolev was not just the creator of 'practical cosmonautics', but a true artist. Glushko did not have Korolev's artistry, or his leadership abilities. He hadn't studied engineering, but chemistry, radio physics, and dreamed of interplanetary flight. Both men had been in prison, and at different times served one under the other in Germany. The story of the political persecution of these two men didn't have to be told, according to Isayev. To do so would only put the film-makers in the camp of enemies of the state.

Later, as Chertok and Isayev viewed the immense 30-engine N1 moon rocket in its assembly building at Baikonur, they mused over all the personal animosities and problems that had led to this unworkable configuration. In the film, life was simple -- and the story ended with the death of Bashkirtsev. But life went on, and was filled with difficult issues never dreamt of in the script. Isayev recollected the compromise that Glushko had offered to Korolev when he was designing the N1. If Korolev would retain the parallel staging scheme used for the R-7, Glushko would promise to deliver within five years a 600 metric ton thrust storable propellant motor for use in the four strap-on booster stages. Mishin killed the deal. He simply would not believe Glushko that even a 170 metric ton thrust motor using liquid oxygen-kerosene could not be developed in the same time scale. Isayev reminded Chertok not to breathe a word of this controversy to Khrabrovitsky -- it was all still a state secret. So no hint of it appeared in the script.

In the film Ada Rogovtseva played Natasha, Bashkirtsev's wife. But he loves his rockets, not her. In the end, he realizes he cannot live without her. Chertok told Khrabrovitsky that this was nonsense that had nothing to do with the life of Korolev. "By God", he complained, "in life Korolev had a wife and one daughter, Natasha, while in the film he has a wife named Natasha and one son".

Khrabrovitsky wanted to film not just launch of R-7 vehicles at Baikonur, but a launch vehicle explosion as well. This did not sit well with the head of the Strategic Rocket Forces, Marshal Krylov, who was in any case opposed to manned spaceflight and this romanticization of the whole topic. The argument on what Mosfilm would be allowed to film and show went all the way to Ustinov. Finally it was decided to give Khrabrovitsky relative freedom, but the VPK Military-Industrial Commission would review the footage before the release of the film. So during 1970-1971 Khrabrovitsky, his photographer Sergei Vronsky, and their crew set up to film key scenes at Baikonur. Up to October 1970 the main launch complex at Area 1 was being refurbished and updated and all launches took place from Area 31. With a launch rate of nearly two Voskhod or Molniya boosters a month, they were able to obtain good shots relatively quickly. No booster co-operated in exploding for the crews, so a booster explosion was staged in the field of debris traps just north of the launch complex. The actors being shown blown into a trench by the force of the explosion.

When the time came to view the first cut in early 1971, the viewing was restricted to Ustinov, and the film consultants Chertok, Grigoryev, and Isayev. No Chief Designers were allowed to attend. The film was screened together with its American counterpart 'Marooned'. The US film showed the head of their space program, Gregory Peck, alone, in isolation, and emphasized the technical aspects of spaceflight. In 'Taming the Fire', on the other hand, the important organizational role of the Communist Party in achieving success was explored. Ustinov was deeply moved by the screening. He was ebullient, shook Khrabrovitsky's hand, congratulated him on his triumph. He gushed "this is the life of Korolev as it would have been were there no controversy with Glushko. Too bad they were not such friends in life as Bashkirtsev and Ognev are in the film". Isayev agreed, "the N1 wouldn't be in such a mess" if life could imitate art.

Ustinov wanted to share the film immediately with Brezhnev and the Politburo. Isayev died suddenly and unexpectedly in the awful month of June 1971, the same month in which the third N1 exploded and the Soyuz 11 crew perished while returning from the Salyut 1 space station. If ever there was a need for the Soviet public to regain its faith in their space program, this was it. When the film was released in 1972, the names of Chertok and Patrushev were altered in the credits to keep their identities secret (to 'Tsvigun' and 'Kostyuk'). This was an ironic twist on the use of 'substitute' names for the characters in the film as well. The names of Isayev, who was now deceased, and Griogoriev, were unaltered. The film was a big success in Russia, with 27 million admissions. It won the Crystal Globe at the Karlovy Vary International Film Festival in 1972 prizes and the First Prize at the All-Union Film Festival in Alma Alta in 1973. The film went on to be a staple of Soviet and Russian television, being shown every year on Cosmonautics Day (April 12). Although dubbed and released in East European countries, it seems never to have been shown in the West.

Synopsis from the East German film prospectus, 1972:

Taming of the Fire -- the first Soviet motion picture concerning the Road to Space.

The life of an extraordinary man in an extraordinary land is portrayed in the new Soviet color film "Taming of the Fire"' by Daniil Khrabrovitsky. It is the first motion picture from the Soviet Union concerning rocket engineering and space research. It is a film telling the story of the men who made it their life's objective to open the Road to Space for the first socialist country on earth. The sensational theme of the film is only exceeded by the nature of the production itself -- a large part was filmed at the Baikonur cosmodrome. Sergei Vronski and his camera team were allowed unprecedented access to film Soviet rockets struggling to reach space, taking men to unimaginable adventures. This creates a unique atmosphere, giving the viewer an entirely new experience. "Taming of the Fire" is a great film, and not just in format and length. It encompasses -- as noted in Pravda -- an important epoch in Soviet history, from Magnitka to Gagarin. It tells first-hand the exciting and suspenseful destiny of the rocket designer Andrei Bashkirtsev, played by Kirill Lavrov.

While Soviet rocket designer Sergei Korolev was undoubtedly the source for this character, the filmmaker has combined in Bashkirtsev elements of many scientists of this type. The film begins with Bashkirtsev placed in a situation requiring a fatal decision, one that will demonstrate his character within a few minutes. Just before the launch of a rocket, sensors indicate many parameters have deviated from the norm. The decision must be taken to accept the risk and proceed with a launch, or to scrub it at great expense and delay to the program. Bashkirtsev has faith in his design and his personal inspection and control of the rocket during its construction. He wants to take the risk, but is overruled. But he is certain of the reliability of his rocket, and the potential waste of time and money literally sickens him. He never gives up and immediately appeals to Moscow - his last chance for a reasonable decision. The scene shows his powerful, self-confident (but for his associates often difficult) personality.

The film dissolves to Bashkirtsev's past. He begins as a youth with home-built aircraft, with all the attendant mistakes and failures. He travels to Magnitogorsk, and meets the old rocket designer Karashev. This inspires him to begin his first research with a group of enthusiasts. They build model rockets, searching for technical solutions through long nights in unheated rooms. Finally there is the meeting with Tsiolkovskiy (brilliantly played by Innokenti Smoktunovsky), who instills in Bashkirtsev the dream of building the first rocket to reach outer space.

After studying with a jet fighter designer, Bashkirtsev becomes directly involved in weapons production during World War II. He is involved in design of the feared Katyusha artillery rocket. In the last years of the war he again turns to design of larger rockets, which have the potential to be, at the same time, the greatest and most tragic consequence of scientific research. Deeply moving scenes flash by showing the struggle to reach space -- launch failures, explosions of rockets in their first seconds of flight, the constant search for the reasons for the failures (irrespective of where the investigation might lead), the despair of setbacks, and the trust of the party in the knowledge and intelligence of the scientists.

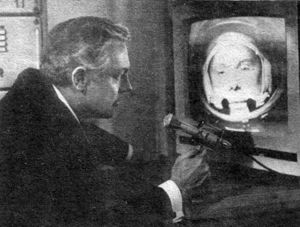

One of the finest film moments comes in the depiction of undiluted joy at the first successful rocket launch and the first flight of a man in space. In a festive procession the cosmonaut is led to the spacecraft. This is followed by the nearly unbearable tension of the launch. Finally there is the joy of accomplishment, the pride in having the strength and will to have achieved all.

The life that Bashkirtsev lives is involving but also often oppressive. Everything is subordinated to work. He is always pressing the limits of the possible. In concentrating on his plans and objectives he forgets his private life. He neglects the wife that he loves, and to whom he is everything. She leaves him, believing that he does not need her. Alone she raises his son, of whom he only learns of years later. In the end he realizes that a part of his life has become empty. He finally realizes that in addition to work other things are necessary for a complete life.

Natasha, the wife that loves him, is played by Ada Rogovzeva, known from "Salute, Maria!" Her self-control allows her to handle the difficult problem of adaptation and subordination in living together with such a difficult husband. At the same time she has to keep a personal life and maintain good relations with other people, and in this special case, with the party.

The film also considers other themes. Can a person accomplish great things without complete concentration on their work? Is life with such a concentration on work and denial of the private sphere really of value? One must also consider the qualities that make Bashkirtsev extraordinary. He is uncompromising, ready to assume responsibility, hard on himself and others, decisive, and completely trusts the abilities of himself and others.

Although the film considers mainly these themes, and has few secondary plot lines outside of the life of Bashkirtsev, one must wonder that such men exist. Men such men who can perform so much, accomplish such great feats, who are utterly selfless, who must go ever farther, always seeking to reach new shores of science, and who can only reach an end to their infinite quest with their own death.

-- Helga Radmann, Moscow

Director Daniil Khrabrovitsky on his film:

In my films 'Nine Days of a Year' and 'Taming of the Fire' I have dealt with nuclear physicists and rocket designers because they are at the leading edge. Men such as Gusev (in 'Nine Days of a Year') and Bashkirtsev are like torches that burn intensely and then flame out. Perhaps in this one can understand the logic of their lives. In that burning, they light the way for mankind. From their work, that can be used for good or evil, depends the fate of the earth. A spectrum of many questions is displayed. The rocket, that can take man into space, can also deliver nuclear weapons.

Many accuse me of tendentiousness, but I don't hold my political views back. I tell passionately of my heroes, who are Communists and use all their strength in the service of their homeland.

The main concept of my hero Bashkirtsev, is the pathos of his work, that to be happy, that he has to overcome enormous problems, even when that goes against his personal interests. It goes directly to the self-mastery of a person, to keep to his objectives, that makes for essential human qualities.

The fate of Bashkirtsev is typical for an entire generation of Soviet men. It cannot be separated from the fate of the people. He is a type of scientists that did not sit in an ivory tower, but rather were servants of the state. He has the characteristic of many men that I know, that obsession that distinguishes many of our people.

I have the feeling that I have prepared for this film my entire life. That does not mean the technical aspects, but rather the human and moral dimensions. I am convinced that the fundamental theme of film art must be the development of mankind. That is for me the essential path of film art, and I will follow this course to find my themes and make my films.

Credits

Taming of the Fire (1972)

(Ukroshcheniye ognya, Russian, Baendigung des Feuers, German)

Runtime: 166 min.

Directed and written by Daniil Khrabrovitsky

Music: Andrei Petrov

Cinematography: Sergei Vronsky

Editor: Mariya Timofeyeva

Production Design: Yuri Kladiyenko

Costume Design: Natalya Firsov

Technical Consultants: (as named in film: A Isayev, M Grigoryev, S Tsvigun, M Kostyuk)

Technical Consultants: (actual: Aleksei Mikhailovich Isayev (Chief Designer, OKB-3), Mikhail Grigoryevich Grigoryev (Deputy Chief of Staff of the Rocket Forces, acting on behalf of Nikolai Ivanovich Krylov, Commander-in-Chief Strategic Missile Forces), Vladimir Semenovich Patrushev (Commander for Launch Operations at Baikonur), Boris Yevseyevich Chertok (Deputy Chief Designer, OKB-1)

Cast:

Kirill Lavrov .... Andrei Bashkirtsev (Korolev)

Ada Rogovtseva .... Natasha

Igor Gorbachyov .... Ognev (Glushko)

Igor Vladimirov .... Golovin

Andrei Popov .... Logunov (Ustinov)

Innokenti Smoktunovsky … Tsiolkovskiy

Vsevolod Safonov … Stretensky (Voskresenskiy)

Zinovi Gerdt … Kartashev

Svetlana Korkoshko … Konstantinova

Igor Petrovsky … Kostromin

Pyotr Shelokhonov … Karelin

Nosheri Chonichvili … Official of the State Commission

with:

I. Bargi

Nikolai Barmin

Vladimir Deyanov

V. Kharkov

A. Kobanadze

Galiks Kolchitsky

Vera Kuznetsova

Yuri Leonidov

Aleksandr Lukyanov

L. Lyndin

Yevgeni Matveyev

A. Mirotov

Vladlen Paulus

Ivan Ryzhov

Vsevolod Safonov

Galina Samokhina

Georgi Shevtsov

Vadim Spiridonov

Yevgeni Steblov

Vitali Velyakov

Admissions: 27,600,000 (Soviet Union)

Karlovy Vary International Film Festival Crystal Globe Award, 1972

Many thanks to Ralf Buelow for suggesting this article and making available a copy of the 1972 film brochure!

Primary sources: the film brochure and Volume 4 of Boris Chertok's memoirs Raketi i lyudi, Mashinostroyenia, Moscow, 1999.

As of August 2011 this movie could be viewed on youtube at ????????? ???? / 1972.

| Taming of the Fire The young Bashkirtsev (Korolev) survives a crash of his primitive glider design in 'Taming of the Fire'. |

| Taming of the Fire Earlier Soviet rocketry at GIRD as reconstructed by Isayev for 'Taming of the Fire'. |

| Taming of the Fire Death of an early rocketry pioneer as portrayed in 'Taming of the Fire'. |

| Taming of the Fire Bashkirtsev (Korolev)'s wedding with Natasha as filmed for 'Taming of the Fire' |

| Taming of the Fire Bashkirtsev (Korolev) receives his life's inspiration from Tsiolkovskiy in 'Taming of the Fire'. |

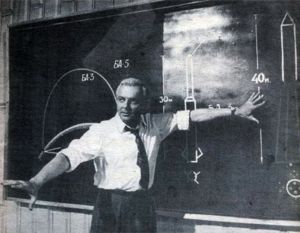

| Taming of the Fire Bashkirtsev (Korolev) lectures on the design progression from the V-2 to the BA-3 (R-5) to the BA-5 (R-7) ICBM in 'Taming of the Fire'. |

| Taming of the Fire Natasha and Bashkirtsev (Korolev) consider their marriage in 'Taming of the Fire'. |

| Taming of the Fire Bukhra (Korolev) and Ognev (Glushko) as portrayed in 'Taming of the Fire' |

| Taming of the Fire Bashkirtsev (Korolev) and Natasha in 'Taming of the Fire'. |

| Taming of the Fire Bashkirtsev (Korolev) argues with launch director over allowing launch of a critical mission in the 'Taming of the Fire'. |

| Taming of the Fire Bashkirtsev (Korolev) receives Kremlin honours after a successful launch in 'Taming of the Fire'. |

| Taming of the Fire Flight of Gagarin as portrayed in 'Taming of the Fire' |

| Taming of the Fire Voskhod launch (red filter) as filmed for 'Taming of the Fire' |

Back to top of page

Home - Search - Browse - Alphabetic Index: 0- 1- 2- 3- 4- 5- 6- 7- 8- 9

A- B- C- D- E- F- G- H- I- J- K- L- M- N- O- P- Q- R- S- T- U- V- W- X- Y- Z

© 1997-2019 Mark Wade - Contact

© / Conditions for Use